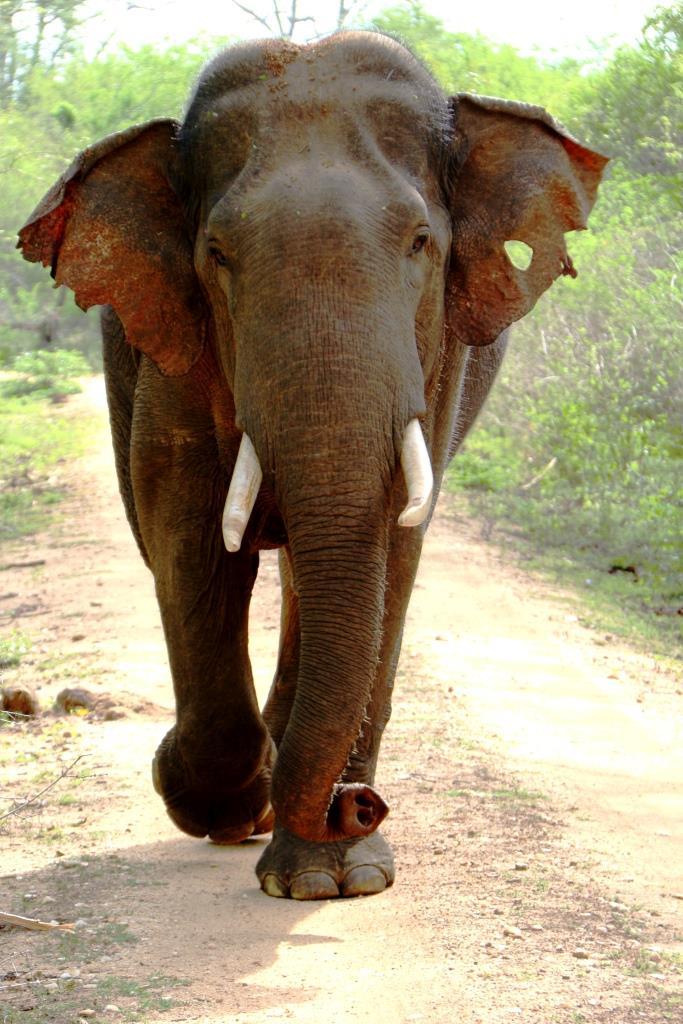

Wild Elephant Deaths in Sri Lanka

By Srilal Miththapala

January 2024

Wild elephant deaths have been increasing alarmingly over the past few years, and reached an all-time peak of 473 in 2023. This translates to more than one elephant being killed per day. Sri Lanka has now earned the dubious ranking as the country where the largest number of Elephants are killed because of the Human Elephant Conflict (HEC).

I believe there are multiple reasons for the increase in HEC. Unplanned alienation of land (for agricultural and other use), clearing and fragmentation of forests, increased human settlements without any planning, human encroachment (permanent or transient) into sensitive areas and political interference in conservation efforts by the Department of Wildlife (DWC) are the main issues.

Basically less land is available for elephants, resulting in their ranging patterns getting disturbed, and bringing them more into contact with people. Studies have indicated that close to 70% of the wild elephants live outside the protected areas.

The main ways in which elephants are killed are by-

- Shooting: Mainly by villagers using shot guns to keep marauding wild elephants at bay. Most often these guns are not sophisticated and high powered, resulting in the elephant sustaining serious injuries, which aggravate over time, resulting in long drawn out suffering and eventual death. Of course the villagers have to be protected and properly located and designed electric fencing appears the best solution as of now.

- Jaw Bombs: These are traps set by the villagers to kill wild boar, where some fruit is laced with explosives which is detonated by a pressure switch. Wild elephants accidently bite on such traps resulting in severe damage to their jaws, and eventually have a gruesome death. These devices must be banned and those who use them must be fined heavily.

- Train accidents: Mostly confined to two or three stretches on the north, and north eastern railway lines. Speed restrictions have not worked partially due to non-compliance and also the difficult layout of the tracks with several bends where early sightings are difficult to make. With today’s technology available, an effective simple early warning system could be easily designed and tested if there is an effort from the relevant authorities.

There has been some talk about the waning population and the fear that the species will be wiped out. However there is no proper study that has been done to support this. Counting elephants is a complex task. The last national census was in 2019 and indicated that there were “5,879 elephants, including 122 tuskers”. No wild elephant census can give an accurate result. More than actual numbers, actual assessment of family groups, juveniles and adolescents, male female ratios, health and body conditions of individuals, would be more useful for good scientific assessment of the exact situation. More of concern is that most often it is the virile, mature males (who range much more than family groups) who are killed, thereby reducing the healthy reproducing stock.

There is no one ‘magic bullet’ to resolve the HEC unfortunately. It is a complex problem that cannot be addressed piecemeal. A sustained, well planned out, focused holistic plan has to be implemented on multiple fronts. This must be led from the very top of the government hierarchy to ensure compliance.

Currently HE the President has appointed a committee to oversee the implementation of the action plans. Certainly this committee is doing what it can under the circumstances.

If we are to stem the ongoing carnage of this valuable natural asset Sri Lanka has been blessed with, immediate action must be taken NOW. A full time task force with all authority and resources has to be appointed under the direct purview of the Presidential Secretariat, to ensue strict implementation of the agreed mitigation plan.